To celebrate, to commemorate: Chris Hogwood (1941 – 2014)

We were all deeply saddened to learn of the untimely death of Chris Hogwood last month. His was a delightful presence when he visited the UL Music Department and he is much missed. Others have eloquently expressed his seminal role in the establishment of historically informed performance, so what we would like to do in this little celebration of his life is to share some personal memories.

“My earliest memories of Christopher Hogwood” says Richard Andrewes, former Pendlebury Librarian and Head of Music at the University Library, “are from my undergraduate days as a member of the Cambridge University Music Club, when he performed at their concerts in the Old University Music School in Downing Place on Saturday evenings in 1964-1965. At that time his interest in early music was greatly encouraged by Charles Cudworth, the Curator of the Pendlebury Library of Music and an acknowledged authority on English music of the 18th century. When I took over from Charles in 1974 Christopher was a regular user of both the Pendlebury and the University Libraries whenever he was in Cambridge.”

“When the international IAML conference met in Cambridge in 1980″, Richard continues, “one of the musical highlights was a concert by the relatively newly formed Academy of Ancient Music in the Senate House performing chamber versions of Haydn symphonies with Christopher at the forte piano and Judith Nelson singing Haydn’s English canzonets. Christopher was also the natural choice of celebrity to open the major exhibition “Keeping the score” celebrating the music collections in the University Library in January 2007. Not only was he a great supporter and user of the Cambridge music libraries, but a great collector of instruments, pictures, books and music.”

John Turner has sent us this delightful vignette:

“In October 1961 I came up to Fitzwilliam House (then in a rabbit warren of a building opposite the Fitzwilliam Museum) to read law, but hoping, as a young flautist and enthusiastic recorder player, to partake fully in the musical life of the College. Alas, musical life in Fitzwilliam was then pretty scanty, with only one undergraduate in the two years above me reading music (so Peter Tranchell, as Fitzbilly’s Director of Studies in Music, was fairly invisible to me). I hasten to add that things soon bucked up, as in my year there was Nicholas Marshall, the composer, and in the following year the NYO clarinettist and future conductor David Atherton – and of course today music in the College in its Storey’s Way / Huntingdon Road site flourishes abundantly.

So initially I felt bereft of musical stimulation. My saviour was Chris, whose digs were just round the corner at no. 1 Fitzwilliam Street, on the ground floor, and he could often be seen through the window playing his clavichord. My first performance in Cambridge was arranged by Chris, and we played together the Frank Martin Sonata da Chiesa for flute and organ in the Round Church (perhaps Bach as well, but I now forget the details of the programme).

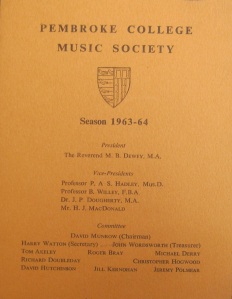

It was of course Chris who introduced me to musicians at Pembroke College, including John Fletcher (then playing horn but subsequently to become the country’s leading tuba player) and particularly David Munrow, who changed the course of my life. I played in several of the intimate concerts put on by the Dean, Meredith Dewey. Chris had a passion for the clavichord at that time, and even persuaded me, along with Jerome Roche, Bill Eden, Julia Hadingham (now Usher) and others to write him pieces, which I hope are now destroyed!

Our connection continued after I left Cambridge and qualified as a solicitor, through David Munrow’s Early Music Consort of London, of which he was a founding member, along with James Bowman, Oliver Brookes and Mary Remnant, and I remember a happy afternoon at Chris’s house playing through numerous flute duets on baroque flutes with Nick McGegan, and discussing his plan to found a British orchestra of original instruments, for which with my legal hat on I prepared the initial constitution. Early AAM recordings in which I played, of Purcell theatre music, the Handel Water Music and La Resurrezione, the Telemann recorder and flute concerto, and the Bach E flat Magnificat, are very happy memories. Playing with Chris was always a joy – he just let the music speak for itself and relied on his players’ instincts. He never imposed his own views on the other performers, though his speeds were sometimes niftier than one might expect! Performances and recording sessions were fun, and I still recall Chris’s infectious giggle.

I remember too how we together discovered the Handel Trio Sonata for two recorders and continuo. He was commissioned by Radio 3 to arrange a series of programmes on the baroque trio sonata, to be accompanied by a BBC Music Guide. He asked me what I would like to play, and I suggested two items unearthed by Bob Dart in the Fitzwilliam Handel collection – a short Allegro for two recorders (apparently without continuo), and an Adagio and Giga for two recorders and continuo, both published by Schott. Chris then recalled that Charles Cudworth had given him a copy of a MS in the Library of Congress, which purported to be a Handel Trio Sonata for two recorders, but lacked one of the recorder parts, which Cudworth had suggested he try to reconstruct. We both realised that by marrying the Fitzwilliam and Library of Congress MSS the complete trio sonata was revealed, and so we gave the first performance in over 250 years in those broadcasts. When Faber subsequently published the first complete edition, edited by Chris, he gave me a copy inscribed in red ink in his distinctive and bold hand – “Thanks for starting this one off.” I am proud to have done so!”

Susi Woodhouse, one of our volunteers here in the Music Department, also has memories of Chris from the time she was an undergraduate at Newnham in the early 1970s: “I remember being completely beguiled by a series of seminars given by Chris, Alan Hacker and Philippa Davis on the history of musical instruments. This must have been just at the time when he was establishing the Academy of Ancient Music and Chris’s wonderful ability to communicate his enthusiasm for and interest in the subject had me hooked from the word go.”

“Librarians aren’t supposed to have favourites” says Margaret Jones, one of the Music Library team at the UL, “but Christopher was one of mine. He was always endlessly enthusiastic, polite, and a joy to work with. My abiding memory of him though is of laughter. He came in one day to order a score, but was looking very perplexed, so I asked him what was wrong:

CH: I’d like to order a score….but I can’t remember who it’s by.

MJ: Well, can you remember the title?

CH: No….

MJ: Or the medium?

CH: (thinks)….No…..

MJ: How about when it was written?

CH: (thinks)….No…. (brightens) But it did have a sort of Laura Ashley wallpaper cover!

And I knew what he meant! Although unfortunately every score in that particular facsimile series had a Laura Ashley wallpaper cover. I don’t think we ever did find the “lost” score, but they’ve been known to the department as the Laura-Ashley-Christopher-Hogwood-facsimiles ever since.”

RMA/MJ/JT/SW

Coda: all the programmes with which we have illustrated this post are drawn from collections held here at the University Library.

“My earliest memories of Christopher Hogwood” says Richard Andrewes, former Pendlebury Librarian and Head of Music at the University Library, “are from my undergraduate days as a member of the Cambridge University Music Club, when he performed at their concerts in the Old University Music School in Downing Place on Saturday evenings in 1964-1965. At that time his interest in early music was greatly encouraged by Charles Cudworth, the Curator of the Pendlebury Library of Music and an acknowledged authority on English music of the 18th century. When I took over from Charles in 1974 Christopher was a regular user of both the Pendlebury and the University Libraries whenever he was in Cambridge.”

Charles Cudworth’s copy of the Pembroke May Week programme. Chris Hogwood provided the continuo.

© Cambridge University Library.

© Cambridge University Library.

Programme for the 1980 IAML Congress given by Chris Hogwood and the AAM.

© Cambridge University Library.

© Cambridge University Library.

“When the international IAML conference met in Cambridge in 1980″, Richard continues, “one of the musical highlights was a concert by the relatively newly formed Academy of Ancient Music in the Senate House performing chamber versions of Haydn symphonies with Christopher at the forte piano and Judith Nelson singing Haydn’s English canzonets. Christopher was also the natural choice of celebrity to open the major exhibition “Keeping the score” celebrating the music collections in the University Library in January 2007. Not only was he a great supporter and user of the Cambridge music libraries, but a great collector of instruments, pictures, books and music.”

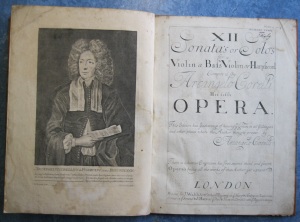

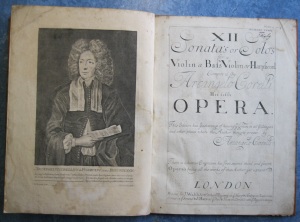

Walsh’s edition of Corelli’s op.5, from the F. T. Arnold bequest [MR360.a.70.9]. A modern edition by Chris Hogwood was published in 2013.

© Cambridge University Library.

© Cambridge University Library.

“In October 1961 I came up to Fitzwilliam House (then in a rabbit warren of a building opposite the Fitzwilliam Museum) to read law, but hoping, as a young flautist and enthusiastic recorder player, to partake fully in the musical life of the College. Alas, musical life in Fitzwilliam was then pretty scanty, with only one undergraduate in the two years above me reading music (so Peter Tranchell, as Fitzbilly’s Director of Studies in Music, was fairly invisible to me). I hasten to add that things soon bucked up, as in my year there was Nicholas Marshall, the composer, and in the following year the NYO clarinettist and future conductor David Atherton – and of course today music in the College in its Storey’s Way / Huntingdon Road site flourishes abundantly.

So initially I felt bereft of musical stimulation. My saviour was Chris, whose digs were just round the corner at no. 1 Fitzwilliam Street, on the ground floor, and he could often be seen through the window playing his clavichord. My first performance in Cambridge was arranged by Chris, and we played together the Frank Martin Sonata da Chiesa for flute and organ in the Round Church (perhaps Bach as well, but I now forget the details of the programme).

Undergrads Christopher Hogwood and David Munrow.

With kind permission of Gillian Munrow.

With kind permission of Gillian Munrow.

Jesus College’s summer concert for 1970 given by the Early Music Consort.

© Cambridge University Library.

© Cambridge University Library.

It was of course Chris who introduced me to musicians at Pembroke College, including John Fletcher (then playing horn but subsequently to become the country’s leading tuba player) and particularly David Munrow, who changed the course of my life. I played in several of the intimate concerts put on by the Dean, Meredith Dewey. Chris had a passion for the clavichord at that time, and even persuaded me, along with Jerome Roche, Bill Eden, Julia Hadingham (now Usher) and others to write him pieces, which I hope are now destroyed!

Our connection continued after I left Cambridge and qualified as a solicitor, through David Munrow’s Early Music Consort of London, of which he was a founding member, along with James Bowman, Oliver Brookes and Mary Remnant, and I remember a happy afternoon at Chris’s house playing through numerous flute duets on baroque flutes with Nick McGegan, and discussing his plan to found a British orchestra of original instruments, for which with my legal hat on I prepared the initial constitution. Early AAM recordings in which I played, of Purcell theatre music, the Handel Water Music and La Resurrezione, the Telemann recorder and flute concerto, and the Bach E flat Magnificat, are very happy memories. Playing with Chris was always a joy – he just let the music speak for itself and relied on his players’ instincts. He never imposed his own views on the other performers, though his speeds were sometimes niftier than one might expect! Performances and recording sessions were fun, and I still recall Chris’s infectious giggle.

A young man going places. Chris Hogwood on Graduation Day.

By kind permission of Gill Munrow.

By kind permission of Gill Munrow.

Susi Woodhouse, one of our volunteers here in the Music Department, also has memories of Chris from the time she was an undergraduate at Newnham in the early 1970s: “I remember being completely beguiled by a series of seminars given by Chris, Alan Hacker and Philippa Davis on the history of musical instruments. This must have been just at the time when he was establishing the Academy of Ancient Music and Chris’s wonderful ability to communicate his enthusiasm for and interest in the subject had me hooked from the word go.”

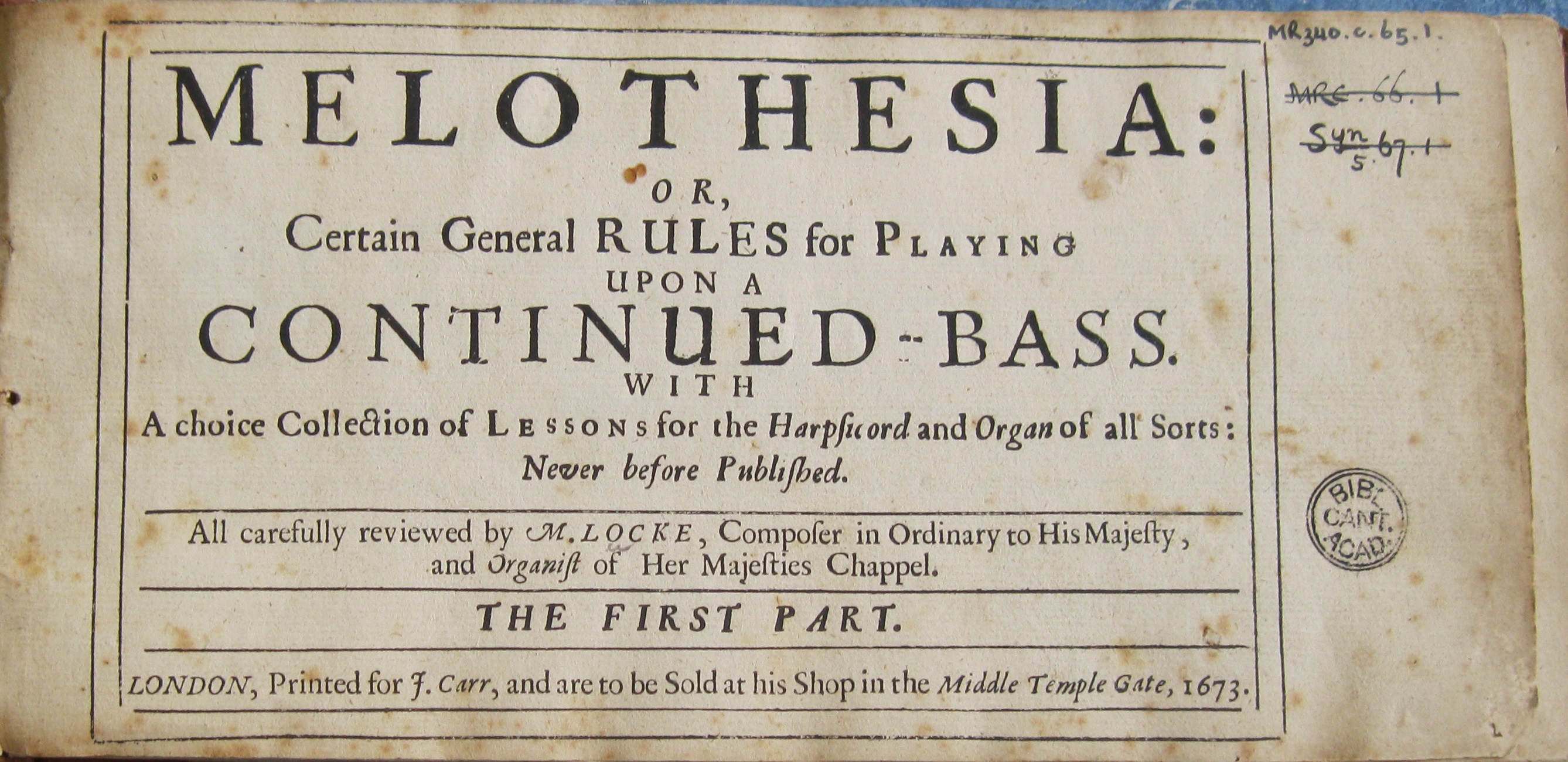

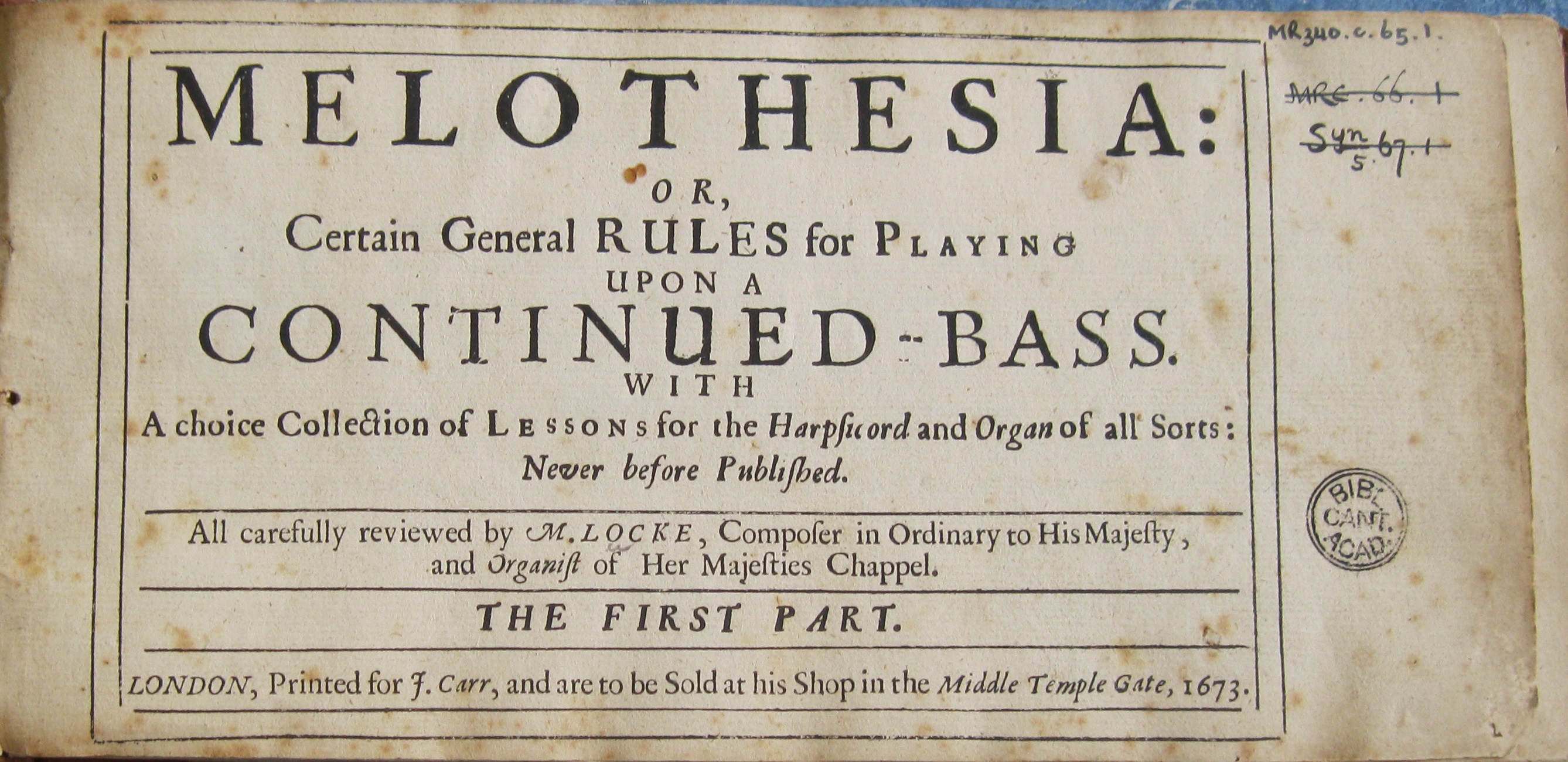

Melothesia, edited by Matthew Locke. [MR340.c.65.1].

OUP published a modern edition in 1987 edited by Chris Hogwood. [ M340.a.95.532]

© Cambridge University Library.

OUP published a modern edition in 1987 edited by Chris Hogwood. [ M340.a.95.532]

© Cambridge University Library.

CH: I’d like to order a score….but I can’t remember who it’s by.

MJ: Well, can you remember the title?

CH: No….

MJ: Or the medium?

CH: (thinks)….No…..

MJ: How about when it was written?

CH: (thinks)….No…. (brightens) But it did have a sort of Laura Ashley wallpaper cover!

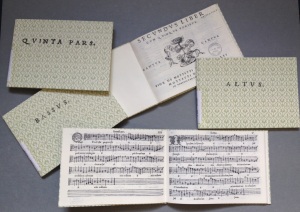

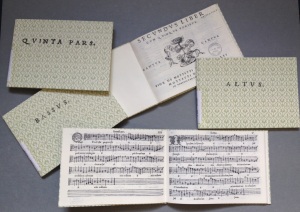

Selections from “Motteti del fiore” originally pubished by Antonio Gardane in Venice. An item in the “Laura Ashley” facsimile series published by Cornetto. MR230.e.200.5-9.

©Cambridge University Library

©Cambridge University Library

Sir John Hawkins’ 1770 history of the original Academy of Ancient Music. [MR470.d.75.3]. Chris Hogwood provided an introduction to a facsimile edition published in 1998. [B1999.1212]

© Cambridge University Library.

© Cambridge University Library.

RMA/MJ/JT/SW

Coda: all the programmes with which we have illustrated this post are drawn from collections held here at the University Library.

Comments

Post a Comment