From the archive: David Munrow profile - 'not even Mick Jagger has such versatile lips'

A Treasury of Early Music http://youtube.com/Searle8

9 March 1971/ The Guardian. Meirion Bowen on the scholar, virtuosic musician and crumhorn whizzkid at the forefront of the period-instrument movement, who died tragically young 40 years ago

There has been no lack of early music specialists in this century, ranging from the Dolmetsch family to Noah Greenberg and the New York Pro Musica. Munrow seems to me to possess most of the scholarly virtues, but in addition, a concern and ability to communicate similar to that shown by Thurston Dart in his concerts of baroque music given during the fifties. Few musicians are better equipped than Munrow to demonstrate that the crumhorns and shawms of medieval and Renaissance music are fit to he appreciated not merely by antiquarians but by the public at large, from the humblest

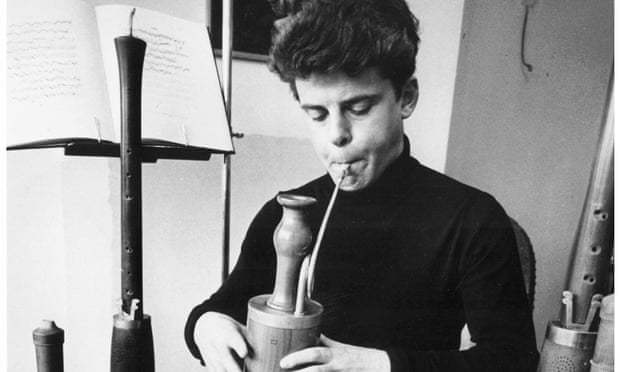

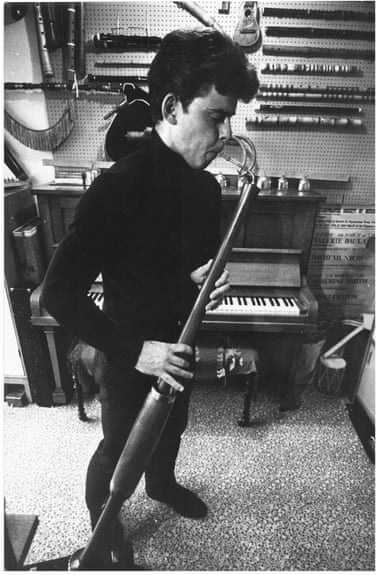

For a start, Munrow is a staggering performer on early woodwind instruments of all sizes and descriptions. When I first visited him in Stratford a few years back, his collection numbered over 150 instruments, and it has grown since then. Moreover he plays them all.

Virtuoso is an unfortunate and overworked epithet which Munrow would hate to have applied to him. And it’s true that a keen ear can spot occasional flaws in his articulation or phrasing, especially since his improvised decoration of fast music is sometimes far too ambitious – it can obscure the sense of the melodic line. But when all’s said and done, how else could one indicate the wizardry with which he will change from shawm to dulcian to cornamuse to gemshorn to rauschpfeife to recorder to crumhorn to kortholt . . . (need I say et cetera) ... launching off immediately in each case with little or no preparation. Not even Mick Jagger can have such versatile lips.

You have only to attend one of the hundreds of lecture-recitals on early woodwind instruments which Munrow gives up and down the country, and abroad, every year to realise how much his playing has caused such instruments to be taken seriously – to be thought of not merely as musical fossils, but as a range of sonorities that hold unlimited delights for the listener, and which today’s composers can find an invaluable stimulus. If you can’t get to one of his lecture recitals, then his exciting new demonstration disc, The Medieval Sound on the Oryx label, will serve the purpose: though seeing him play these colourful instruments inevitably adds further dimension.

Munrow was not born with a sopranino rauschpfeife in his mouth. But his musical aspirations did develop early on. He took piano lessons from the age of six and (more important) sang in Birmingham Cathedral Choir, an experience that opened vistas on to music for him. When his voice broke he sought refuge in playing the recorder and bassoon, though school (King Edward VI Birmingham) provided little incentive to pursue a musical career. His first contact with the world of medieval instruments came on leaving school to spend a year teaching in South America. There he came across many of the instruments associated with medieval music in a context where they were still the staple diet of music, were still played with a total lack of inhibition, with a careeningly free sense of improvisation.

Some of Munrow’s many wind-instruments date back to this South American trip. Others have been acquired elsewhere in the course of his travels – from tiny villages in Europe to hippie shops in California. Most of his collection consists of modern reconstructions based on pictures or other information. (The makers are largely German – like Otto Steinkopf, Rainer, Weber. etc. – but there are now some English ones springing up, like Jim Jones.) The freshness and spontaneity of Munrow’s playing, however, are undoubtedly to some extent a product of hearing such instruments within folk-cultures where the most ancient musical practices survive to this day. Medieval music has never for him been a dead art exhumed by scholars. It is alive and well and flourishing all over the world.

Returned from South America, Munrow went to Cambridge, where he sang in Jesus College choir, and met Thurston Dart. Dart encouraged him to exploit to the full his potential as a specialist on early woodwind instruments. Munrow did so, primarily playing with his friends, those with whom it was sheer enjoyment to make music. This is an important aspect of Munrow’s approach, something on which his later achievements have depended considerably. His Early Music Consort, formed in 1967, developed out of such friendly music-making with Christopher Hogwood (harpsichord), Oliver Brookes (viol), and James Bowman (counter-tenor), and is a remarkably integrated and polished ensemble. In no time, the Consort was reckoned a front-rank group.

The Consort’s success does not depend entirely on brilliant performances. Its programmes are planned to run with perfect smoothness, with a precise awareness of what the audience needs to know or hear at any given moment. Introductions – either spoken or included in the programme – are invariably informative, witty, and often deliciously obscene as well. What people don’t generally realise is that the very idea of giving a concert of early music is unauthentic, a falsification of what originally happened. To present, therefore, a recital of four centuries’ dance music, as Munrow did a few weeks back, becomes a creative act in itself (as my colleague. Hugo Cole, so rightly pointed out).

Munrow has enlarged the Consort considerably for his Renaissance Festival programme, and his ideas have come off equally well on the larger canvas. For many people, Munrow’s name will always be associated with performances of a set of dances by Tielman Susato (a 16th-century composer who flourished as player, publisher, and composer at Antwerp. and who had a shop with the sign “In de Kroomhoorn”) that have often ended his Festival programmes. He first mounted performances of these dances at Cambridge and at Birmingham University (where he spent a year researching after finishing at Cambridge): the concluding battle-piece has always won him an ovation not just for its extra decibels, but because each time he scores it differently, preserving its raw freshness and potency. It is good news that he has just recorded these dances for EMI.

For some time he was a member of the Stratford Wind Ensemble and his contributions to drama productions extended into radio, television, and films. David Cain wrote music for him to play for the BBC radio serial of Tolkien’s The Hobbit. More recently television viewers will have heard the music he provided for The Six Wives of Henry VIII series and in the sequel. Elizabeth R, as well as at the V and A Exhibition. He is becoming difficult to dodge, likely to crop up as the indispensable background to some display or exhibition or in collaboration with a folk group.

Anyone who tries to pin down Munrow to any one category of work is doomed to failure. He is not just the crumhorn whizzkid. (Mind you, more ponderous medievalists underestimate his scholarship.) His skill as a deviser of recital programmes has stood him in good stead recently on the radio, when he introduced a series of Afternoon Sequences – two hours of records for Saturday afternoons on Radio 3. He is always on the move. His wife. Gillian, does all the planning of transport, food, and accommodation.

She also plays percussion and bells in their lecture-recitals: and the whole operation makes great demands on her energy and patience. Without such support Munrow would probably not have become so prominent and colourful a figure on the concert scene by the age of 28. And it’s a good thing he’s a small chap. otherwise there’d be no room in the car for him along with all those coffin-like cases containing racketts, crumhorns, recorders. shawms, clans, rauschpfeifes, kortholts, gemshorn....

Comments

Post a Comment